What makes cancer so dangerous? Cancer cells that leave the primary tumor to reach distant sites of the body where they may grow into daughter tumors, called metastases. While most primary tumors can be effectively treated, metastases are the real danger. Oncologists estimate that more than 90 percent of all cancer deaths in solid tumors are due to metastases.

Researchers have been working for decades to understand and prevent the spread of tumor cells. However, the mechanisms that enable a cancer cell to survive in a distant organ and ultimately grow into a metastasis are still largely unknown.

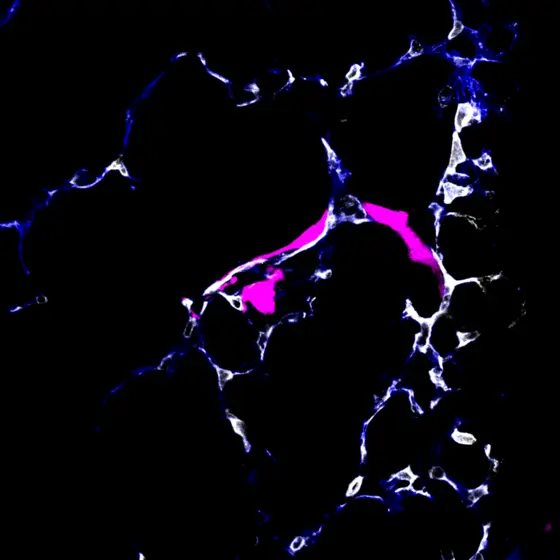

To spread throughout the body, cancer cells travel through blood and lymphatic system. Scientists at the DKFZ and at Heidelberg University have now developed a method to observe the behavior of migrating cancer cells in mice immediately upon arrival in the metastatic organ - in this case the lung.

The team led by the two first authors Moritz Jakab and Ki Hong Lee discovered that some tumor cells, once they have arrived in the metastatic organ, leave the blood vessel and enter a resting state. Other cancer cells start to divide directly within the blood vessel and grow into metastases.

This delicate fate decision of the metastasizing tumor cells is controlled by the endothelial cells that line the inside of all blood vessels. They release factors from the Wnt signaling pathway that promote the exit of tumor cells from the blood vessel and thereby initiate latency. When the researchers switched off the Wnt factors, latency no longer occurred.

What distinguishes latent from growing metastasizing cancer cells?

“At this point, we asked ourselves the question: Why do some cancer cells immediately form a metastasis, while others fall into a kind of sleep?“ says Moritz Jakab. The dormant and metastasizing cancer cells did not differ genetically, nor in many other molecular aspects. But the researchers were able to detect a subtle difference: The methylation of the DNA differed between the two cell types. Tumor cells, whose DNA was less methylated, responded sensitively to the Wnt factors, which resulted in extravasation from the blood vessel and subsequent latency. On the other hand, the more methylated cancer cells did not respond to the Wnt factors, remained in the blood vessel and immediately started metastatic growth.

DNA methylation is part of the epigenetic memory that is passed on to daughter cells during cell division. The methylation status of a cell is therefore largely stable. This led the researchers to suspect that the metastatic behavior of the cancer cells may already be determined when they detach from the primary tumor.

To test this hypothesis, the team examined the DNA methylation status of various tumor cell lines. Indeed, they found that this directly correlated with their metastatic potential.

“These results are surprising and could have far-reaching consequences for tumor diagnosis and therapy. The results of the study could, for example, help to use certain methylation patterns as biomarkers to predict for patients how high the load of dormant cancer cells is and, thus, how likely the patient is to relapse after successful treatment of the primary tumor,“ says senior author Hellmut Augustin. “But first we need to study whether natural human tumors behave in the same way as the employed cell lines or experimental tumors.“

Moritz Jakab, Ki Hong Lee, Alexey Uvarovkii, Svetlana Ovchinnikova, Shubharda L Kulkarni; Sevinc Jakab, Till Rostalski, Carleen Spegg, Simon Anders, Hellmut Augustin: Lung endothelium exploits suscepible tumour cell states to instruct metastatic latency.

Nature Cancer, 2024, https://www.nature.com/articles/s43018-023-00716-7