Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins and key nutrients for cell growth and proliferation. Understanding how cells utilise amino acids in different environments is a central question in basic biology and cancer research. Tumor tissues often have a limited blood supply, and to grow under such conditions, cancer cells switch their metabolic activities. In particular, they switch from taking up nutrients delivered by blood vessels to exploiting alternative nutrients, such as breaking down surrounding proteins as a food source when facing starvation. However, the mechanisms that enable cancer cells to make this switch have remained largely elusive.

To better understand the molecular pathways that underly this nutrient switch in cancer, two groups of scientists with matching expertise teamed up: Wilhelm Palm of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg is a leading expert in cancer metabolism, Johannes Zuber at the Research Institute of Molecular Pathology (IMP) in Vienna brought in ample experience in functional cancer genetics. The scientists set up their study with tightly controlled nutrient conditions to mimic amino acid starvation as it occurs in many tumors. Then they used the “gene scissors“ CRISPR-Cas9 to disrupt the expression of almost every gene in the genome, which allowed them to pin down several pathways involved in the nutrient switch.

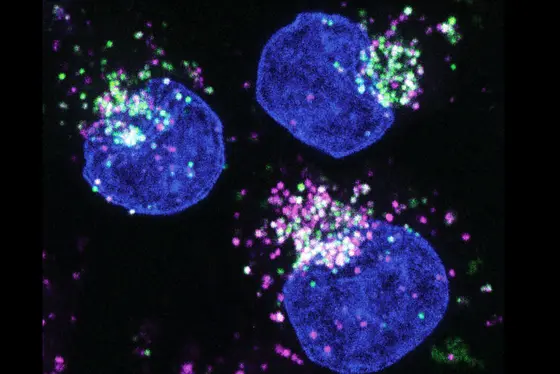

Among them, the scientists spotted an uncharacterised gene that was only required for cell survival when cancer cells were feeding on extracellular proteins. This gene, which the scientists re-named “LYSET“ (Lysosomal Enzyme Trafficking Factor), turned out to be critical for the function of lysosomes, small organelles that function as the stomach of cells where proteins are digested. Further experiments into the function of LYSET revealed that the gene acts as a core component of the so-called mannose-6-phosphate pathway, which is required for filling lysosomes with digestive enzymes. In the absence of LYSET, cancer cells lack enzymes in their lysosomes and are no longer able to digest proteins.

Then the scientists turned to mouse models to study the function of LYSET in real tumors. They found that the loss of LYSET strongly impaired tumor development in several types of cancer, while it was well-tolerated under normal nutrient conditions.

Wilhelm Palm, whose lab was among the first who described the ability of cancer cells to feed on extracellular proteins, says: “With LYSET, we have discovered a central component of a metabolic pathway that enables adaptations to different nutrients, a key ability of cancer cells to survive and grow in austere Tumor environments.“

“This is what made the discovery so exciting,“ says Johannes Zuber. “LYSET and the mannose-6-phosphate pathway turn out to be particularly important for cancer cells and could therefore be a molecular entry point for attacking a major metabolic bottleneck in cancer.“

Original Publication

Catarina Pechincha, Sven Groessl, Robert Kalis, Melanie de Almeida, Andrea Zanotti, Marten Wittmann, Martin Schneider, Rafael P. de Campos, Sarah Rieser, Marlene Brandstetter, Alexander Schleiffer, Karin Müller-Decker, Dominic Helm, Sabrina Jabs, David Haselbach, Marius K. Lemberg, Johannes Zuber, Wilhelm Palm: Lysosomal enzyme trafficking factor LYSET enables nutritional usage of extracellular proteins.

Science, 2022, doi.org/10.1126/science.abn5637

A picture is available for download:

Illustration-dq-lysotracker.jpg

Figure Captions

Human cancer cells (cell nucleus in blue) feeding on protein (Albumin, labelled in green). The proteins are digested and broken down into amino acids in the lysosomes (magenta).

Note on use of images related to press releases

Use is free of charge. The German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) permits one-time use in the context of reporting about the topic covered in the press release. Images have to be cited as follows: “Source: W. Palm / DKFZ“.

Distribution of images to third parties is not permitted unless prior consent has been obtained from DKFZ's Press Office (phone: ++49-(0)6221 42 2854, E-mail: presse@dkfz.de). Any commercial use is prohibited.