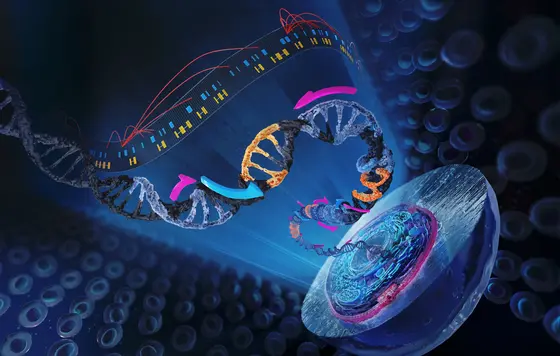

Tens of thousands of tiny genetic variations (SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphisms) have been identified in the human genome that are associated with specific diseases. Many of these genetic variants are not located in the protein-coding regions of genes, but affect regulatory sections. Therefore, scientists are trying to find out if and in which tissues these variants can be linked to changes in the activity of specific genes.

Typically, such analyses are performed in blood cells or tissue biopsies, depending on the type of disease. “Pluripotent stem cells, however, might be better suited for this purpose in many cases, as they are undifferentiated and therefore reflect the ancestral state of all cells,“ says Oliver Stegle, division head at the German Cancer Research Center and group leader at EMBL. “Stem cells could be particularly relevant when searching for the cause of diseases that occur early in development.“ Pluripotent stem cells can be generated in the culture dish from normal body cells obtained from a blood sample, for example. They are referred to as “induced pluripotent stem cells,“ or iPSCs for short, since they are not naturally occurring stem cells.

Together with scientists from Stanford University and additional international cooperation partners, Oliver Stegle's team has compiled sequence and transcriptome data on iPSCs from around 1000 donors. The researchers systematically examined these data to identify correlations between individual genetic variants and altered expression patterns in stem cells. The results have now been published in the journal Nature Genetics.

For more than 67 percent of all genes active in iPSCs, the researchers found differential expression patterns depending on genetic variants. Many of these associations are novel and have not been described in somatic cell types before. For over 4000 of these associations, the genetic variants responsible for the altered expression patterns could be linked to specific diseases. These included, for example, variants associated with coronary heart disease, lipid metabolism disorders or hereditary cancers.

Stegle and colleagues also investigated whether iPS are suitable for identifying the causative genes of rare genetic diseases. They used iPSC lines from 65 patients who suffered from various rare diseases, whose causal gene defects were already known through previous analyses. In the transcriptome data of these iPSC lines, the scientists searched for particularly conspicuous “outliers“ in the expression pattern. These analyses reliably led to the trace of the genetic basis of the disease. “Such screenings were previously impossible because there were simply no sufficiently large reference collections of iPS transcriptomes,“ explained Marc Jan Bonder, first author of the study.

“We were surprised to find such a large number of disease-associated genetic variants that are already visible in the expression pattern at the earliest time point of cell differentiation, represented by the iPSCs“. Until now, the relevance of iPSCs for such biomedical analyses has been significantly underestimated.

In a companion paper, published in the same issue of Nature Genetics, Stegle and colleagues from EMBL-EBI and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute used more than 200 iPSC lines to investigate how genetic variants affect differentiation into neuronal cells.

The scientists performed RNA single-cell sequencing at different time points of neuronal cell differentiation. This allowed them to analyze how genetic variants affect expression patterns in different cellular states, including different neuronal cell types. “The study demonstrates the power of combining single-cell sequencing with iPSC technologies to dissect the effect of genetic variants in cell types that would otherwise be inaccessible,“ Stegle explains.

Bonder, M.J. Smail, C., Gloudemans, M.J., Frésard, L., Jakubosky, D., D'Antonio, M., Li, X., Ferraro, N.M., Carcamo-Orive, I., Mirauta, B., Seaton, D.D., Cai, N., Kilpinen, H., Vakili, D., Horta, D., Wheeler, M.T., Zhao, C., Zastrow, D.B., Bonner, D.E., HipSci Consortium, iPSCORE Consortium, GENESiPS Consortium, PhLiPS Consortium, Undiagnosed Diseases Network, Knowles, J.W., Smith, E.N., Frazer, K.A., Montgomery, S.B., Stegle, O.: Identification of rare and common disease variants using population-scale transcriptomics of pluripotent cells.

Nature Genetics 2021, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00800-7

Jerber, J., Seaton, D.D., Cuomo, A.S.E., Kumasaka, N., Haldane, J., Steer, J., Patel, M., Pearce, D., Andersson, M., Bonder, M.J., Mountjoy, E., Ghoussaini, M., Lancaster, M.A., HipSci Consortium, Marioni, J.C., Merkle, F.T., Gaffney, D.J., Stegle, O: Population-scale single-cell RNA-seq profiling across dopaminergic neuron differentiation

Nature Genetics 2021, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00801-6