If cancer cells detach from a tumor and move around the body, they are entering enemy territory. Many detached cancer cells do actually die before they manage to colonize other tissues and form metastases, because the body's immune system is geared toward protecting healthy tissue from intruders of all kinds. Moreover, these migrant cancer cells can only survive if they manage to manipulate the cells in their new environment to create a metastatic niche that helps the migrant cancer cells survive.

Thordur Oskarsson and his team at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and at the Heidelberg Institute for Stem Cell Technology and Experimental Medicine (HI-STEM gGmbH) are investigating how this metastatic niche arises. The scientists have now discovered both in cell cultures and in mice that some particularly aggressive breast cancer cells induce a situation similar to inflammation in lung tissue. This ultimately ensures that they can colonize the tissue and grow into metastases.

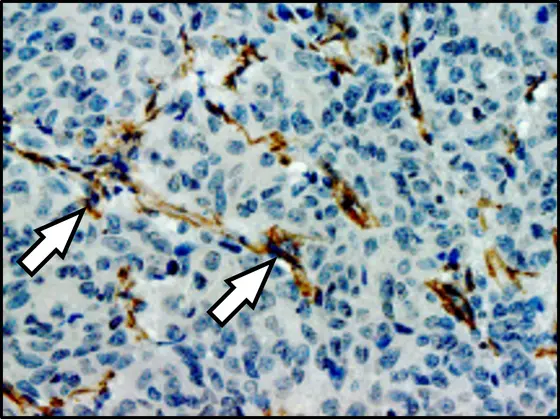

Specifically, the detached tumor cells release two inflammatory signaling molecules, known as interleukins, which stimulate fibroblasts in the lung to release two further inflammatory signaling molecules into the microenvironment: CXCL9 and CXCL10. In turn, these attach to a receptor molecule that several aggressive migrant cancer cells carry on their surface, marking a decisive step in the process of growing into a metastasis. These aggressive breast cancer cells thus benefit directly from the inflammation and from the signaling molecules CXCL9 and CXCL10.

“Interestingly, the very tumor cells that stimulate the fibroblasts to produce CXCL9 and CXCL10 also have the relevant receptor for these cytokines and thus benefit from the process,“ explained Maren Pein, lead author of the study. “That underlines how crucial the cellular communication between the detached cancer cells and the fibroblasts in their new microenvironment is for metastasis.“

Furthermore, the scientists prevented metastasis in the lung in an experimental setting by treating mice with an inhibitor that blocked the receptor molecule on the cancer cells.

Tumor tissue samples from patients show that this cellular interaction probably plays a role in breast cancer patients too: Thus cancer cells that carry the relevant surface receptor and can therefore harness the interaction with fibroblasts to form metastases are also found in patients with metastatic breast cancer.

Oskarsson emphasized that it was still too early to identify a new treatment approach from these findings. “Our work is initially designed to help understand the underlying mechanisms that are necessary for metastases to actually arise,“ he explained. “But we obviously hope that this better understanding will lead to us being able to prevent metastases some time in the future.“

*The Heidelberg Institute for Stem Cell Technology and Experimental Medicine (HI-STEM gGmbH) is a partnership between DKFZ and the Dietmar Hopp Foundation

Maren Pein, Jacob Insua-Rodríguez, Tsunaki Hongu, Angela Riedel, Jasmin Meier, Lena Wiedmann, Kristin Decker, Marieke A.G. Essers, Hans-Peter Sinn, Saskia Spaich, Marc Sütterlin, Andreas Schneeweiss, Andreas Trumpp and Thordur Oskarsson: Metastasis-initiating cells induce and exploit a fibroblast niche to fuel malignant colonization of the lungs

Nature Communications 2002, DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-15188-x

A photo to accompany the press release is available for download at:

https://www.dkfz.de/de/presse/pressemitteilungen/2020/bilder/Lungenmetastase.jpg

Photo caption: Lung metastasis in a breast cancer patient: the arrows indicate fibroblasts (brown) that communicate with metastatic cancer cells. Cell nuclei are stained blue.

Note on use of images related to press releases

Use is free of charge. The German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) permits one-time use in the context of reporting about the topic covered in the press release. Images have to be cited as follows: “Source: Oskarsson, DKFZ/HI-STEM“.

Distribution of images to third parties is not permitted unless prior consent has been obtained from DKFZ's Press Office (phone: ++49-(0)6221 42 2854, E-mail: presse@dkfz.de). Any commercial use is prohibited.