Glioblastomas are the most common malignant brain tumors in adults. Since they invade diffusely into healthy brain tissue, surgeons rarely succeed in completely removing the tumor. Therefore, glioblastomas often recur very quickly despite the radiation and chemotherapy following surgery and are then considered incurable according to current knowledge.

“There was a theory that certain mutations might enable glioblastoma cells to survive standard radiochemotherapy and then grow into resistant subclones of the tumor. Our question was: Does the therapy exert a selection pressure on the tumor cells?“ said Peter Lichter from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) explaining his current research project. For the development of new drugs that are also effective against relapsed tumors, it is crucial to identify genetic traits that enable cancer cells to evade therapy.

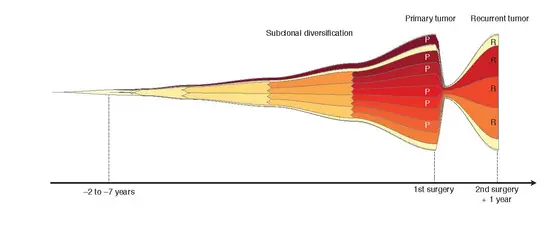

In order to answer this question, Lichter and systems biologist Thomas Höfer from the DKFZ investigated glioblastoma tissue samples from a total of 50 patients in which they were able to directly compare material from the primary tumor and recurrence. Based on a careful analysis of the tumor genome, the researchers were able to develop a mathematical model of tumor development. They used mutation rates and estimates of tumor cell count. “We simulated the evolutionary pathways of glioblastoma cells and the influence of their gene mutations during tumor growth on the computer,“ said Höfer describing the procedure.

The surprising results: At the time of diagnosis, a glioblastoma had already developed over a very long period of time, the researchers calculated up to seven years. “This is hardly conceivable in view of the extremely rapid growth of glioblastomas,“ said Verena Körber, the first author of the current publication. “However, we can explain this by the fact that many cancer cells die at the beginning, only at a certain moment does the rapid growth in size start.

The researchers have also discovered this decisive moment: During their early development, all glioblastomas studied showed at least one of three characteristic genetic alterations (gain of chromosome 7, loss of chromosome 9p and 10). These chromosome losses or gains are associated with known, specific “driver mutations“ that promote the development of cancer.

However the glioblastomas only start with their rapid growth and increase in size when an additional mutation permanently activates one of the promoters for the telomerase. The enzyme telomerase ensures that the cancer cells can now divide infinitely and do not reach their natural limit and die after a certain number of cell divisions. In healthy cells, the telomerase gene is therefore usually not active. During their exponential growth, numerous other mutations accumulate in the cancer cells.

In contrast to the common path of the early developing glioblastomas, the recurrent tumors did not share any characteristically corresponding mutations. They can develop from cancer cells with a variety of different mutation patterns. “This suggests that the current standard therapy does not exert any noticeable selective pressure on the cancer cells and therefore does not promote the development of resistant subclones. This shows that we basically need new forms of treatment in order to effectively treat glioblastomas,“ said Peter Lichter summarizing the current results.

Verena Körber, Jing Yang, Pankaj Barah, Yonghe Wu, Damian Stichel, Zuguang Gu, Michael Nai Chung Fletcher, David Jones, Bettina Hentschel, Katrin Lamszus, Jörg Christian Tonn, Gabriele Schackert, Michael Sabel, Jörg Felsberg, Angela Zacher, Kerstin Kaulich, Daniel Hübschmann, Christel Herold-Mende, Andreas von Deimling, Michael Weller, Bernhard Radlwimmer, Matthias Schlesner, Guido Reifenberger, Thomas Höfer, Peter Lichter: Evolutionary trajectories of IDH-wildtype glioblastomas reveal a common path of early tumorigenesis instigated years ahead of initial diagnosis.

Cancer Cell 2019, DOI: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.02.007