African trypanosomes, the pathogens causing sleeping sickness, are notorious for their ability to escape the body's immune defense. The trick that prevents them from being completely destroyed by the immune cells has been known for decades.

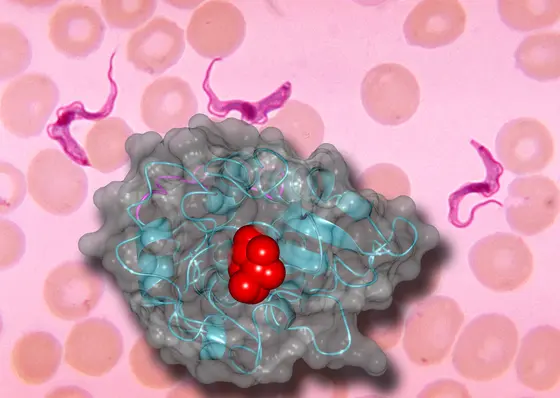

The unicellular parasites are covered by a dense layer of identical proteins, the so-called variable surface glycoproteins (VSGs). Antibodies of the infected human are directed against these proteins and the parasites are largely eliminated as a result. However, occasionally individual pathogens change their surface protein completely. To do this, they simply switch to another VSG gene - they have around a thousand different ones available.

“It's like putting on a new coat,“ says Nina Papavasiliou, immunologist at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ). The trypanosomes masked in this way are no longer recognized by the antibodies, they multiply rapidly, and the infection, which the immune system had initially kept in check, flares up again violently.

“We have assumed for decades that only the modified amino acid building blocks of the new VSGs are responsible for the pathogens escaping the immune system,“ said Erec Stebbins, also at the DKFZ. “But now we have discovered that sugar molecules also play a role and make it even harder for the body's immune system to cope with the parasite.“

Stebbins and his team have now examined various VSGs using X-ray structure analysis. In one of the molecules, VSG3, the researchers discovered binding sites for sugar molecules on the “outside“ facing the immune system. Michael Ferguson from the University of Dundee, Scotland, found out with further analyses that these binding sites are actually occupied with a multitude of different sugars.

In order to find out whether the sugar chains have an influence on the proliferation of parasites or on the success of the immune defense, the scientists around Papavasiliou created trypanosomes whose VSG3 lacked the sugar binding site. While mice infected with normal trypanosomes quickly died of the infection, the animals survived an infection with “sugar-free“ trypanosomes and were able to completely eliminate the pathogen from their blood after a few days.

Vaccinated with sugar-free, inactivated trypanosomes, mice developed a protective immune response. However, the transmission of pathogens with normal VSGs did not trigger any vaccination protection. The researchers found the binding sites for the sugar not only at the VSG3, but also in numerous other VSGs.

“The sugar chains coupled to the VSG do not completely paralyze the immune system. But they are clearly obstructing it. In addition to switching to new VSGs, the different sugar chains are an additional strategy with which the parasites make it difficult for the immune system to eliminate the pathogens,“ explains Papavasiliou.

The researchers are not yet able to say exactly how the sugars hinder the immune system. “They may partially cover the binding sites of antibodies,“ speculates Stebbins and points out that altered sugar molecules can also influence the immune defense of cancer cells: “Sugar molecules are very important recognition structures for the immune system. This applies to the defense of microorganisms as well as to the immune defense of tumors.“

Trypanosoma brucei, the pathogen causing African sleeping sickness, occurs mainly in West and Central Africa. The pathogen transmitted by the tsetse fly attacks the central nervous system and causes severe neurological disorders. Without treatment, infection can lead to death. The number of reported cases last declined, falling by 90 percent between 1999 and 2015, from 28,000 to 2,800 patients (source: Medecins sans Frontieres).

Jason Pinger, Dragana Nešić, Liaqat Ali, Francisco Aresta-Branco, Mirjana Lilic, Shanin Chowdhury, Hee-Sook Kim, Joseph Verdi, Jayne Raper, Michael A. J. Ferguson,F. Nina Papavasiliou and C. Erec Stebbins: African trypanosomes evade immune clearance by O-glycosylation of the VSG surface coat

Nature Microbiology 2018, DOI: 10.1038/s41564-018-0187