The growing number of overweight people has long been one of modern society's pressing issues. In particular the resulting metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes and corresponding secondary conditions can have serious consequences for health. Can a reduced intake of calories help to whip the metabolism back into shape?

This is the question that Adam J. Rose at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) Heidelberg and Stephan Herzig at the Helmholtz Zentrum München, wanted to answer. “Once we understand how fasting influences our metabolism we can attempt to bring about this effect therapeutically,“ Rose states.

Stress molecule reduces the absorption of fatty acids in the liver

In the current study, the scientists looked for liver cell genetic activity differences that were caused by fasting. With the help of so-called transcript arrays, they were able to show that especially the gene for the protein GADD45β was often read differently depending on the diet: the greater the hunger, the more frequently the cells produced the molecule, whose name stands for 'Growth Arrest and DNA Damage-inducible'. As the name says, the molecule was previously associated with the repair of damage to the genetic information and the cell cycle, rather than with metabolic biology.

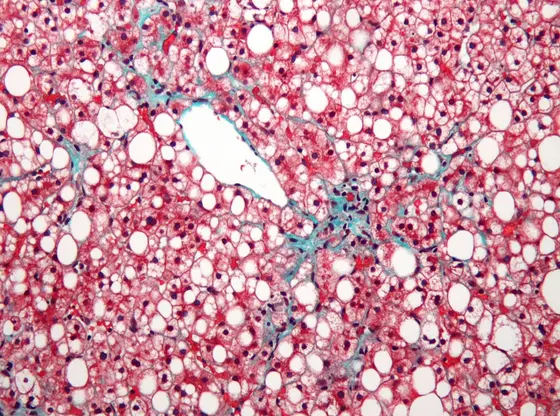

Subsequent simulation tests showed that GADD45β is responsible for controlling the absorption of fatty acids in the liver. Mice who lacked the corresponding gene were more likely to develop fatty liver disease. However when the protein was restored, the fat content of the liver normalized and also sugar metabolism improved. The scientists were able to confirm the result also in humans: a low GADD45β level was accompanied by increased fat accumulation in the liver and an elevated blood sugar level.

“The stress on the liver cells caused by fasting consequently appears to stimulate GADD45β production, which then adjusts the metabolism to the low food intake,“ Herzig summarizes. The researchers now want to use the new findings for therapeutic intervention in the fat and sugar metabolism so that the positive effects of food deprivation might be translated for treatment.

An interview with Stephan Herzig is available at:

https://vimeo.com/164214586

Jessica Fuhrmeister, Annika Zota, Tjeerd P. Sijmonsma, Oksana Seibert, Sahika Cıngır, Kathrin Schmidt, Nicola Vallon, Roldan M de Guia, Katharina Niopek, Mauricio Berriel Diaz, Adriano Maida, Matthias Blüher, Jürgen G. Okun, Stephan Herzig und Adam J. Rose: Fasting-induced liver GADD45β restrains hepatic fatty acid uptake and improves metabolic health, EMBO Molecular Medicine 2016, DOI: 10.15252/emmm.201505801