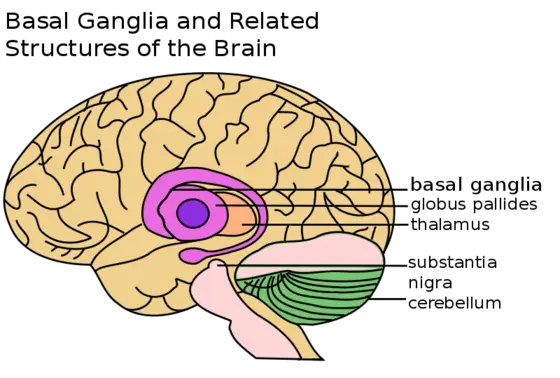

A small area in the midbrain known as the substantia nigra is the control center for all bodily movement. Increasing loss of dopamine-generating neurons in this part of the brain therefore leads to the main symptoms of Parkinson's disease – slowness of movement, rigidity and shaking.

In recent years, there has been increasing scientific evidence suggesting that inflammatory changes in the brain play a major role in Parkinson's. So far, it has been largely unclear whether this inflammation arises inside the brain itself or whether cells of the innate immune system that enter the brain from the bloodstream are also involved.

At the DKFZ, a team led by Prof. Dr. Ana Martin-Villalba is investigating causes of cell death in the central nervous system. Neuroscientist Martin-Villalba has suspected that a specific pair of molecules, the CD95 system, is involved in neuronal death in Parkinson's. This pair consists of the CD95 ligand and its corresponding receptor, CD95, also known as the “death receptor“.

Martin-Villalba recently showed that after spinal cord injury, inflammatory cells use these molecules to migrate to the injury site, where they cause damage to the tissue. Martin-Villalba then wanted to investigate whether peripheral inflammatory cells also play a role in chronic neurodegenerative processes such as Parkinson's disease.

To investigate the process of neurodegeneration in mice, the scientists utilized a model system using the substance MPTP, which causes the selective death of dopamine-generating neurons in the human brain. In mice, MPTP typically causes Parkinson-like symptoms.

However, in mice whose inflammatory cells (monocytes, microglia) were unable to produce CD95L, MPTP treatment resulted in almost no neurodegeneration. This suggested that CD95L-bearing inflammatory cells are involved in the destruction of neurons. However, it remained unclear whether the true culprits are specific macrophages in the brain called microglia, or rather monocytes in the bloodstream that infiltrate the brain.

In order to make this distinction, the investigators used a chemical that blocks CD95L without being able to pass the blood-brain barrier. This substance therefore reaches only the inflammatory cells that circulate in the bloodstream and not the microglia that reside in the brain. Mice that had received this substance were also protected from MPTP-induced neurodegeneration.

“Thus, we have shown for the first time that peripheral inflammatory cells of the innate immune system also play a role in neurodegeneration,“ say Liang Gao and David Brenner, first authors of the publication. “A key role in this process is played by CD95L, which enhances the mobility of these cells.“

Project leader Martin-Villalba speculates that a self-reinforcing vicious cycle arises in the brain: The breakdown of a few neurons that die from various causes attracts inflammatory cells that, in turn, further fuel the death of more neurons through inflammation-promoting signaling molecules.

At present, the researchers can only indirectly conclude that the results obtained in the artificial animal model are also relevant in human Parkinson's disease. In collaboration with colleagues from Ulm, Martin-Villalba’s team recently found elevated quantities of inflammatory monocytes that were hyperactive in blood samples from Parkinson's patients. Monocyte number correlated with the severity of disease symptoms. However, the researchers do not yet know whether these inflammatory cells also migrate into the brains of patients and contribute to the demise of neurons there, like they do in the mice with Parkinson's.

“If this is the case, drugs that inhibit CD95L might mitigate Parkinson's symptoms if administered early on – similar to what we observed in our experimental mice,“ says Martin-Villalba. The substance required for this has already been investigated in clinical Phase II trials. Martin-Villalba also suspects that activated cells of the peripheral immune system might drive neurodegeneration not only in Parkinson's disease but also in other neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's.

Gao L., D. Brenner, E. Llorens-Bobadilla, G. Castro-Saiz , T. Frank, P. Wieghofer, O. Hill, M. Thiemann, S. Karray, M. Prinz, J. Weishaupt, and A. Martin-Villalba. Infiltration of circulating myeloid cells through CD95L contributes to neurodegeneration in mice. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2015, DOI: 10.1084/jem.20132423.

Grozdanov, V., C. Bliederhaeuser, W.P. Ruf, V. Roth, K. Fundel-Clemens, L. Zondler, D. Brenner, A. Martin-Villalba, B. Hengerer, J. Kassubek, A.C. Ludolph, J.H. Weishaupt, and K.M. Danzer: Inflammatory dysregulation of blood monocytes in Parkinson’s disease patients. Acta Neuropathol. 2014, DOI:10.1007/s00401-014-1345-4.