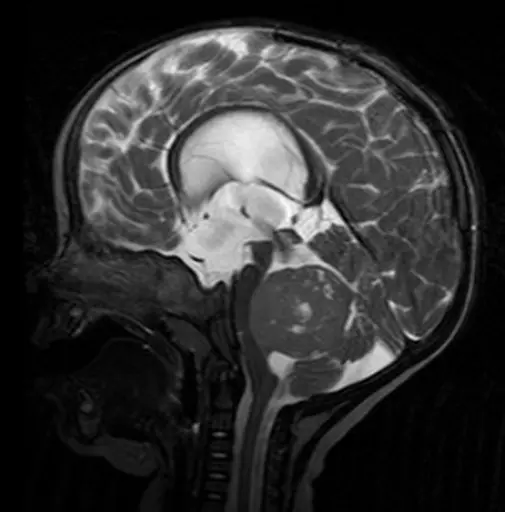

Medulloblastoma is the most common childhood brain tumor. It is classified in four distinct subgroups that vary strongly in terns of the aggressiveness of the disease. Group 3 and Group 4 tumors, which are very challenging, are particularly common. “For these two tumor groups, hardly any characteristic genomic changes that drive tumor growth and would make potential targets for drug development have been identified,“ says Prof. Dr. Peter Lichter from the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ), who is coordinator of the PedBrain Tumor network. The PedBrain network is part of the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC), whose researchers are systematically analyzing all genomic alterations in pediatric brain cancer to discover new targets for the development of gentler modes of treatment.

Dr. Paul Northcott and coworkers from the first team took a closer look at 137 cases of the more aggressive Group 3 and Group 4 medulloblastomas. They discovered a phenomenon that had never been observed before in brain cancer. In many of the tumor genomes, large regions of DNA had been deleted or duplicated or had changed their orientation. Despite their different nature, these structural changes had identical consequences in all tumors under investigation: One of two oncogenes called GFI1 and GFI1B, which are not active in healthy brain tissue, is transcribed in these tumors and thus contributes to the development of cancer.

The PedBrain researchers also discovered what causes this strange phenomenon. Various structural changes had moved the oncogene from a usually inactive environment to a position close to DNA sequences called “enhancers", which are involved in the activation of genes. In mice, the researchers subsequently proved that activated GFI1B leads to the development of brain cancer, providing evidence that the “hijacked“ gene enhancers promote the onset of cancer.

“It is quite possible that hijacked enhancers also play a role as activating mechanisms in many other types of cancer," says Prof. Dr. Stefan Pfister, a molecular geneticist at the DKFZ, who also works as a pediatrician at Heidelberg University Hospital. “However, one can only discover them through a very careful analysis of the genome, and therefore they are easily missed."

The researchers are particularly pleased that their work may directly contribute to the development of better treatments for children with brain cancer. Substances that block the effects of the GFI1 and GFI1B oncogenes are already being tested in clinical trials and might now also be used to slow down the growth of aggressive Group 3 and Group 4 medulloblastomas.

The second team focused their investigations on the so-called “epigenetic" regulation of gene activity by chemical labels in DNA. The researchers compared patterns of DNA methylation across the whole genome from 42 medulloblastomas with the patterns found in healthy control tissue.

The number of methylation groups found in the promoter region, i.e., the region of DNA that stimulates the transcription of a gene, has been considered a crucial factor in gene activity. For the first time, Volker Hovestadt and his colleagues have discovered that altered methyl groups within genes also are also relevant to their activation. Numerous genes in tumor cells exhibited low levels of methylation compared to healthy counterparts. At the same time, they were transcribed significantly more frequently than in healthy cells. This is clear evidence that a lack of methyl groups has functional effects.

“The regulation of gene activity by methyl labels within a particular gene has never been observed, at least not to such a marked extent," Lichter says. “In some of the tumors we found nearly 1000 genes that were methylated at lower levels than their counterparts in healthy cells."

PedBrain network coordinator Lichter summarized the relevance of the two Nature publications: “The results show the major relevance of the epigenetic regulation of genes, including known oncogenes, in medulloblastoma. In addition, we have identified GFl1 and GFl1B as an Achilles’ heel of the most dangerous types of medulloblastoma. For the first time, this reveals a molecular weak spot in these tumors that can be targeted in drug development."

The International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC), a network of scientists currently from 16 countries, aims to obtain a comprehensive description of genomic and epigenomic changes in all significant cancer types. With the PedBrain Tumor Project, German scientists are analyzing pediatric brain tumors (medulloblastoma and pilocytic astrocytoma). Within the project, 500 samples of pediatric brain tumors will be analyzed along with the same number of samples of healthy tissue from the same patients, to identify changes that are specific to cancer.

The PedBrain Tumor network consists of researchers from seven institutes led by project coordinators Peter Lichter (DKFZ) and Roland Eils (DKFZ, Heidelberg University). Participating project partners in Heidelberg include the DKFZ, the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT), Heidelberg University and the University Hospital, and the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL). In addition, scientists from Düsseldorf University Hospital and the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin have taken on tasks in the network project.

The German Cancer Aid (Deutsche Krebshilfe) provided funds of eight million Euros for PedBrain Tumor. Since July 1, 2012, the project has received another seven million Euros from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

Volker Hovestadt, David T. W. Jones, …, Bernhard Radlwimmer, Stefan M. Pfister und Peter Lichter im Auftrag des ICGC PedBrain Tumor Project: Decoding the regulatory landscape of medulloblastoma using DNA methylation sequencing. Nature 2014, DOI: 10.1038/nature13268

Paul A Northcott, Catherine Lee, Thomas Zichner, …, Peter Lichter, Jan O Korbel, Robert J Wechsler-Reya und Stefan M Pfister im Auftrag des ICGC PedBrain Tumor Project:Enhancer hijacking activates GFI1 family oncogenes in medulloblastoma. Nature 2014, DOI:10.1038/nature13379