Over 90 percent of the world population is infected with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Fortunately, only a fraction of those who are infected actually develop a disease. In most cases, the virus persists unnoticed in the body throughout a person’s lifetime – provided that his or her immune system is intact. However, there are cases where it causes various diseases: in Europe and North America, it leads to infectious mononucleosis (Pfeiffer’s disease); in Central Africa it causes Burkitt's lymphoma; and nasopharyngeal cancer is a common result in Southeast Asia.

So far, it has been unclear why EBV infections take such diverse courses. In Africa, simultaneous infection with the parasite that causes malaria may induce Burkitt’s lymphoma. The age of an initial infection is believed to play a role in infectious mononucleosis, and in China, substances in people’s diet seemed to promote nasopharyngeal cancer.

“Scientists have known that there are differences in the genetic material of the various viruses that occur worldwide," says Henri-Jacques Delecluse of the German Cancer Research Center. “We have now been able to show for the first time, with help from colleagues from Zurich, that these genetic differences are actually responsible for the diverging properties that the viruses exhibit in terms of promoting disease."

Delecluse and his coworkers initially isolated viral DNA from two patients: one from North America who suffered from infectious mononucleosis; the other was a man from Hong Kong who suffered from nasopharyngeal cancer. The DKFZ scientists discovered that the two virus strains had important differences: The virus from the Chinese cancer patient is particularly efficient in infecting epithelial cells of the mucous membranes, while that of the American patient suffering from infectious mononucleosis infects only B cells of the immune system.

“Although Epstein-Barr viruses can be found in the epithelial cells of nasopharyngeal carcinomas, researchers have been puzzled by its behavior in the laboratory," Delecleuse says. “They haven’t been able to infect these cells with EBV, or have had to use tricks to do so. “Now we know that the laboratory strains were completely different from those that were isolated from cancer patients."

Delecluse expects that his findings will be a major step toward preventing virus-induced cancers in the future. “We are currently developing a vaccine based on so-called ‘virus-like particles’, or VLPs. These are empty virus shells that can prompt the body to mount an immune response." VLPs are already being used successfully in vaccines against human papillomaviruses and hepatitis B viruses. “We previously believed that the Epstein-Barr virus is one and the same around the world. Now we know that there are different strains; in our efforts to develop vaccines, we should focus on strains that seem to be particularly aggressive."

Ming-Han Tsai, Ana Raykova, Olaf Klinke, Katharina Bernhardt, Kathrin Gärtner, Carol S. Leung, Karsten Geletneky, Serkan Sertel, Christian Münz, Regina Feederle and Henri-Jacques Delecluse: Spontaneous lytic replication and epitheliotropism define an Epstein-Barr virus strain found in carcinomas. Cell Reports, DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.09.012

A picture for this press release is available on the Internet at:

epstein-barr-virus.jpg

Caption:

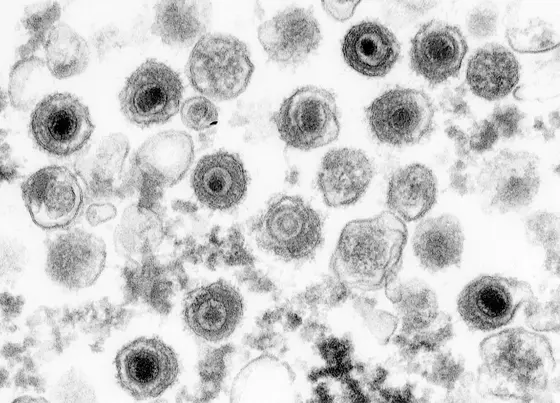

Electron micrograph picture of Epstein-Barr viruses