For a malignant tumor to form, cancer cells must evade an attack by the immune system. Numerous studies have shown that cancer spreads particularly aggressively if there is an unfavorable balance between suppressing and active immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. “But we didn’t know whether this is a consequence of an aggressive tumor or rather its cause," says Rudolf Kaaks, epidemiologist at the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ).

Kaaks and his co-workers had a unique opportunity to pursue this question: The DKFZ in Heidelberg is a study center of the EPIC study, a project devoted to investigating the links between diet and cancer in almost half a million people throughout Europe. In initial EPIC examinations carried out from 1996 to 1998, blood samples were taken from all study participants and subsequently frozen. From the 25,000 participants in Heidelberg, the researchers now selected the blood samples from about 1,000 individuals who had developed cancer in the course of the observation period (including lung cancer, colon cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer). A group of 800 participants who were not affected by a malignancy was used as a control.

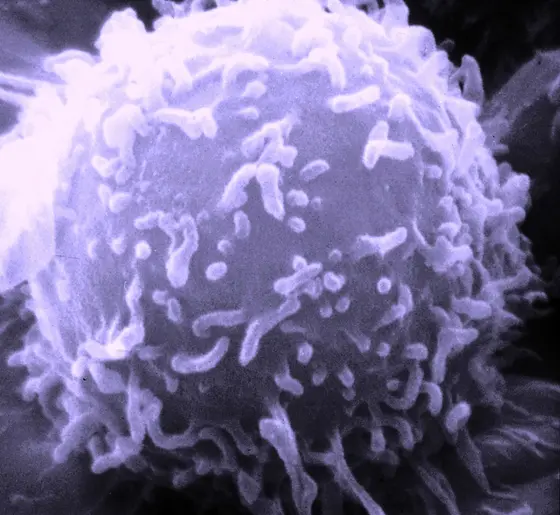

Sebastian Dietmar Barth and his colleagues from Kaak’s department counted suppressive regulatory T cells in the blood samples and determined the ratio of these cells to the total number of T cells, which also comprise the tumor-fighting cells. This ratio is called “immunoCRIT". As a rule, the higher the immunoCRIT value, the more the immune system is being suppressed.

When comparing EPIC participants with extremely high or extremely low immunoCRIT values, the researchers found that with a strong increase, the risk of lung cancer rises by 100 percent, and the risk of colon cancer by approximately 60 percent. Women with very high immunoCRIT values experience an astounding three-fold increase in their risk of developing estrogen-receptor negative breast cancer*. Here, however, the researchers think that number of cases examined might be too low to make a definite statement. In cases of prostate cancer and estrogen-receptor positive breast cancer, the DKFZ epidemiologists found no links between immunoCRIT and cancer risk.

When tumor-fighting T cells are kept in check by regulatory T cells, which have an inhibitory function, scientists speak of “peripheral immune tolerance." “With this study, we have demonstrated for the first time that the unfavorable ratio of immune cells already prevails long before the onset of the disease," Kaaks says. “Hence it is more likely to be the cause than the result of cancer."

The DKFZ researchers conducted this study in collaboration with Epiontis, a Berlin-based company that specializes in the epigenetic tests that were used to determine the ratio of the various T cell populations.

The scientists do not yet know why immune tolerance has an effect on the risks of developing certain types of cancer. A possible explanation may found in the results of prior research: tumors of the lung and bowel tend to be colonized by particularly high quantities of immune cells. The Heidelberg epidemiologists now plan to extend their investigation to other types of tumors.

* Breast cancer whose cells exhibit no receptor proteins for the female sex hormone estrogen.

Sebastian Dietmar Barth, Janika Josephine Schulze, Tilman Kuhn, Eva Raschke, Anika Husing, Theron Johnson, Rudolf Kaaks, Sven Olek: Treg-Mediated Immune Tolerance and the Risk of Solid Cancers: Findings From EPIC-Heidelberg

JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst.2015, DOI: 10.1093/jnci/djv224