Oxidizing chemical compounds called reactive oxygen species (ROS) can be produced as a side product of cellular respiration or inflammatory processes. These reactive molecules (oxidants) can damage components of the cell or cause alterations in DNA. Therefore, levels of oxidants in body cells are strictly controlled and kept very low by antioxidative enzymes.

On the other hand, the body's own oxidants, particularly so-called peroxides, also have communication functions in the cell. They oxidize proteins at particular sites, thus changing their signaling properties. These oxidative signals enable the cell to adapt rapidly to changes in environmental or metabolic conditions.

However, measurements have shown that peroxidases – enzymes which protect the body from oxidative damage by degrading peroxides – work extremely efficiently, such that selective oxidation of signaling proteins should essentially be impossible. Up to now, it had remained enigmatic how oxidation of signaling proteins can take place if oxidants are removed thus efficiently from the cell.

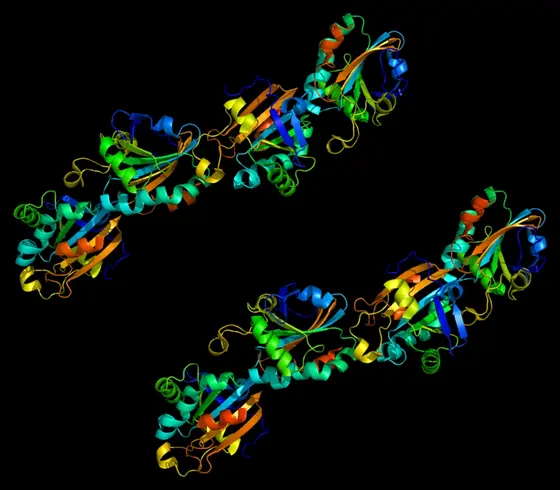

Current results of a research team led by Tobias Dick from the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg have shown that a class of peroxidases called peroxiredoxins has a particular role in cellular signal transduction. Beyond simply removing peroxides and thus protecting the cell from uncontrolled oxidation, they are also capable of transmitting the oxidative effect of peroxides in an orderly manner to signaling proteins.

There appears to be a division of labor: Most peroxiredoxin molecules efficiently and completely remove peroxides, thus protecting the cell as a whole. Small local clusters of the same peroxiredoxins, however, facilitate oxidation of neighboring proteins whose function is regulated by oxidation.

The researchers discovered this by eliminating the genetic information for peroxiredoxins from the genetic material of human cells. Contrary to general expectations, oxidation of cellular proteins did not increase as a result. Instead, the oxidation level of signaling proteins was reduced.

“We observed in this study that in the absence of peroxiredoxins, hardly any signaling proteins are oxidized,“ said Sarah Stöcker, who is the first author of the study. “This means that peroxidases not only prevent the negative effects of oxidant formation, they also mediate their positive function as signals. We now know that peroxidases are global antioxidants on the one hand and local oxidants on the other.“

The new results prompt researchers to rethink the role of antioxidative enzymes in carcinogenesis. “Expression of peroxidases in tumor tissue has often undergone alterations. Until now, cancer researchers have been interested in the consequences of this defect with a view to the antioxidative function,“ Dick said. “Now the question is whether the disrupted communicative function of peroxidases might also play a role in the development of cancer.“

The research project is part of the Collaborative Research Center 1036 (SFB 1036), which pursues research on basic mechanisms of cellular stress response within the DKFZ-ZMBH alliance. The SFB is funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Sarah Stöcker, Michael Maurer, Thomas Ruppert, Tobias P. Dick (2017): A role for 2-Cys peroxiredoxins in facilitating cytosolic protein thiol oxidation.

Nature Chemical Biology 2018, DOI: 10.1038/nchembio.2536