In humans and in mice alike, the abdominal fat of heavily overweight, or obese, individuals is chronically inflamed. The inflammation promotes insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and is also considered to be among the factors which increase the cancer risk of obese people.

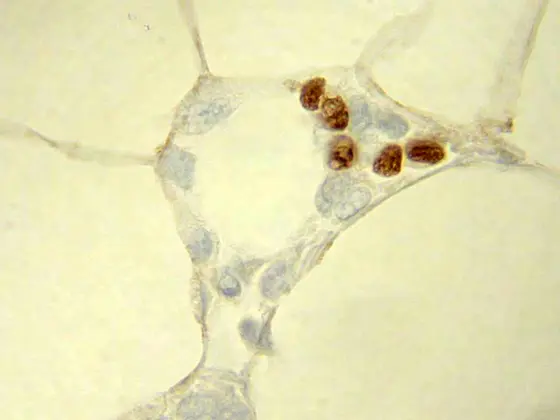

The inflammation is caused by macrophages that move into the abdominal adipose tissue in large numbers. There they release messenger molecules which further fuel inflammatory processes. Dr. Markus Feuerer of DKFZ, who until recently pursued research at Harvard Medical School, made a sensational discovery while working there: In the abdominal fat tissue of mice with normal body weight, he discovered a group of immune cells, called regulatory T cells, which keep the inflammation in check. In the belly fat of obese mice, however, this particular cell population was absent. “When we experimentally increased the number of anti-inflammatory cells in fat mice, the inflammation subsided and glucose metabolism went back to normal," Feuerer said.

In his new work, Markus Feuerer, jointly with his former colleagues from Diane Mathis’ group at Harvard Medical School, identified the nuclear protein PPARγ as the main molecular switch regulating the anti-inflammatory activity of regulatory T cells. The immunologists bred mice with regulatory T cells that are unable to produce PPARγ. In the abdominal fat of these animals, there were almost no anti-inflammatory cells to be found. Instead, there were significantly more inflammation-causing macrophages present than in normal animals.

PPARγ is well known to doctors as the target molecule of a class of antidiabetic drugs: Glitazones, also known as “insulin sensitizers", selectively activate this nuclear receptor. Up to now, physicians have assumed that glitazone improves glucose metabolism mainly by acting on PPARγ in fat cells. Therefore, Markus Feuerer and colleagues first tested whether the drugs also have a direct effect on the anti-inflammatory immune cells. This seems to be the case, because glitazone treatment led to an increase in the number of anti-inflammatory cells in the belly fat of obese mice, while the number of inflammation-promoting macrophages decreased.

Does the effect on the anti-inflammatory T cells possibly even contribute to the therapeutic effect of the drugs? Feuerer’s findings provide evidence for this: In obese mice, glitazone treatment improved metabolic parameters such as glucose tolerance and insulin resistance. In genetically modified animals, whose T cells are unable to produce PPARγ, the drug did not normalize glucose metabolism.

“This is a totally unexpected effect of this well-known group of medications," said Feuerer. First studies have suggested that abdominal fat of humans also has a specific population of regulatory T cells. “But we still need to check whether these cells really reduce the inflammations of the fat tissue and whether we can also influence them using glitazones," the DKFZ immunologist explains. "Another very important finding of our current work is that this was the first time that we have been able to target a specific population of regulatory T cells with a substance. This holds promise for treating many different diseases." The chronic inflammation of fat tissue is also considered to be a growth promoter for many types of cancer. Therefore, cancer researchers are also interested in the possibility of using a drug to control such inflammations.

Daniela Cipolletta, Markus Feuerer, Amy Li, Nozomu Kamei, Jongsoon Lee, Steven E. Shoelson, Christophe Benoist and Diane Mathis: PPARg is a major driver of the accumulation and phenotype of adipose-tissue Treg cells. Nature 2012, DOI: 10.1038/nature11132