Molecular Genetics

- Functional and Structural Genomics

Prof. Dr. Peter Lichter

We are interested in pathomechanisms of tumorigenesis and their relevance for the development of new strategies of tumor diagnosis and therapy.

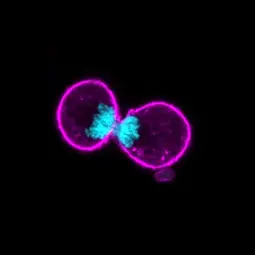

Image: Mitose. Francois L, et al. Cell Reports 2022,

Image: Mitose. Francois L, et al. Cell Reports 2022,

Our research

Our focus is the elucidation of the genetic heterogeneity between and within tumor cell populations. The genetic pattern of neoplastic cells represents a "snapshot" of the clonal or subclonal composition of a tumor, and through appropriate longitudinal analyses we track and model tumor evolution. As the outgrowth of individual tumor cell clones often occurs in dependence on therapeutic measures, we exploit our data and models to develop hypotheses on mechanisms that can lead to resistance to therapy. We test these in preclinical models in vitro and in vivo, including the use of patient-derived cell systems. Ultimately, these approaches serve to successfully counteract therapy resistance.

Tumor heterogeneity interests us on the one hand at the level of neoplastic cells with special focus on mechanisms to maintain genome stability and - more recently - on factors that regulate metabolic processes in the cell. On the other hand, we are interested in the heterogeneity of non-malignant cells in the tumor microenvironment, i.e. the cells of the stroma and immune system. In addition, we investigate the potentially pathogenic role of microorganisms via extensive microbiome analyses in tumor or tumor-near tissue.

For potential clinical applications, we develop and validate predictive markers and gene signatures based on comprehensive molecular profiles of tumor cells at the level of genome, methylome, transcriptome and other classes of molecular and cellular structures. This led to the implementation of an active workflow for Personalized Oncology based on genomic and transcriptomic data, which contributes to alternative or new therapy suggestions in clinical practice within regular Molecular Tumor Boards of the NCT Molecular Precision Oncology program. This workflow is central to the implementation of joint clinical trials for breast cancer patients (https://www.nct-heidelberg.de/fuer-aerzte/tumorentitaeten/gynaekologische-tumorenbrusttumoren/diagnostik-studien.html).

B060 Team

Our Team

-

Prof. Dr. Peter Lichter

Head of division

-

Dr. Bernhard Radlwimmer

Group leader

-

Dr. Martina Seiffert

Group leader

-

Dr. Marc Zapatka

Group leader

Selected Publications

Boscovic P, Wilke N, … Radlwimmer B.

Francois L, Boskovic P ... Lichter P, Radlwimmer B.

Wong JKL, Aichmüller C, … Lichter P, Zapatka M.

Hlevnjak M, Schulze M, Elgaafary S, …, Thewes V, Zapatka M, Lichter P, Schneeweiss A.

Hanna BS, Llaó Cid L, Iskar M, Roessner PM, … Lichter P, Zapatka M, Seiffert M.

Zapatka M, Borozan I, Brewer S, Iskar M, …, Ferretti V, Lichter P, PCAWG Consortium

Sadik A*, Somarribas Patterson LF*, Öztürk S*, Mohapatra SR*, Panitz V, Secker PF, …, Böhme A, Schäuble S, Thedieck K, Trump S*, Seiffert M*, Opitz CA*. *shared authorship

Körber, V. Yang J, Barah P, …, Schlesner M, Reifenberger G, Höfer T, Lichter P.

Northcott PA, Buchhalter I, Morrissy AS, Hovestadt V, Weischenfeldt J, Ehrenberger T, Gröbner S, Segura-Wang M, Zichner T, …, Korbel JO, Brors B, Schlesner M, Eils R, Marra MA, Pfister SM, Taylor MD, Lichter P.

Get in touch with us